2025 NO.38

MenuThe Japanese People and Space

Japanese Views of Outer Space

Since ancient times, outer space has been seen as an extension of nature in Japan, familiar through poems, songs, and tales. Japan’s approach to space development reflects this unique cosmological view, as well.

A scene in Taketori Monogatari Emaki (“The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter Illustrated Scroll”) depicts Princess Kaguya (upper right) departing Earth to return to the moon with her entourage. (Collection of National Diet Library)

The moon, ever close

Taketori Monogatari (“The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter”), the oldest example of Japanese monogatari (fictional prose narrative) literature, written around the 9th century, features a moon-related setting. In it, Princess Kaguya from the moon grows into an adult on Earth before eventually making her return, escaping a marriage proposal from the Emperor, who has fallen in love with her, charmed by her beauty. The tale depicts the impermanent nature of life on Earth and the immortality associated with the world of the moon. Also, the 11th-century Sagoromo Monogatari (“The Tale of Sagoromo”), includes a scene in which protagonist Sagoromo, a mid-ranking captain, is visited by a deity who descends from the moon as he plays his flute in front of the Emperor. These two tales, both depicting visitors from the moon, suggest that the people of Japan viewed celestial bodies not as distant and completely cut off from the Earth, but associated with a considerable degree of closeness.

Outer space as an extension of nature

The Shinto religion, practiced in Japan since ancient times, is based on a belief that all things are imbued with kami spirits — yao-yorozu no kami, “myriads of deities”—including mountains, seas, rivers, and trees. Since the Japanese people have primarily supported their lives with agriculture, the natural world, which they associated with blessings as well as threats, was not only an object of awe and fear, but of reverence. Consequently, celestial bodies were counted among the “myriads of deities,” with the sun deified as Amaterasu Omikami and the moon as Tsukuyomi no Mikoto. While this made them exceptional among the kami deities, they were depicted as having great influence on people’s lives. With the celestial kami viewed as essentially the same as those on Earth, outer space, then, was thought of as an extension of nature.

This Japanese cosmological view has been expressed in poetry and songs as well. The Manyoshu (“Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves”), the oldest Japanese poetry collection, compiled around the 7th to 8th centuries, contains over 100 poems featuring the moon. In the same way as the mountains, rivers, flora, and other natural phenomena the poets took as objects of their emotion, the moon was featured in their work as well. Poet of the Edo period (1603–1868) Matsuo Basho composed the following haiku:

Araumi ya / Sado ni yokotau / Amanogawa

The stormy sea / stretching out toward Sado / the Milky Way

His poem, inspired by natural beauty, places the imagery of the island of Sado floating in the rough waters of the Sea of Japan alongside the Milky Way — Amanogawa, “the Celestial River”—stretching through the skies above. It certainly feels imbued with Japanese sensitivities that view the celestial bodies and nature as an integral whole.

The Milky Way stretches through the skies above the island of Sado, as described in a haiku by Matsuo Basho. (Photo: Aflo)

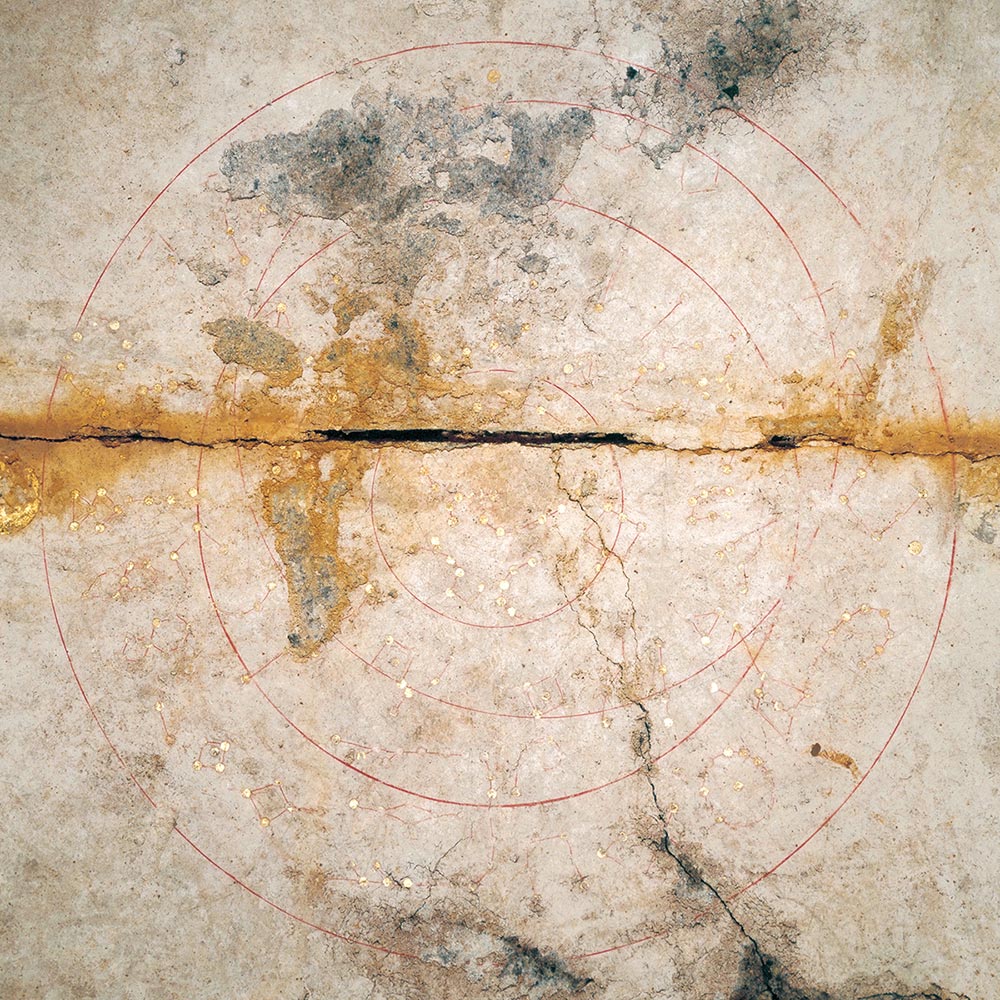

An astronomical chart in the Kitora Tomb includes over 350 stars, as well as circles corresponding to the celestial equator and the ecliptic (the apparent path of the Sun). (Five mural paintings of Kitora Tomb, Jurisdiction of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan)

The historical development of astronomical observation in Japan

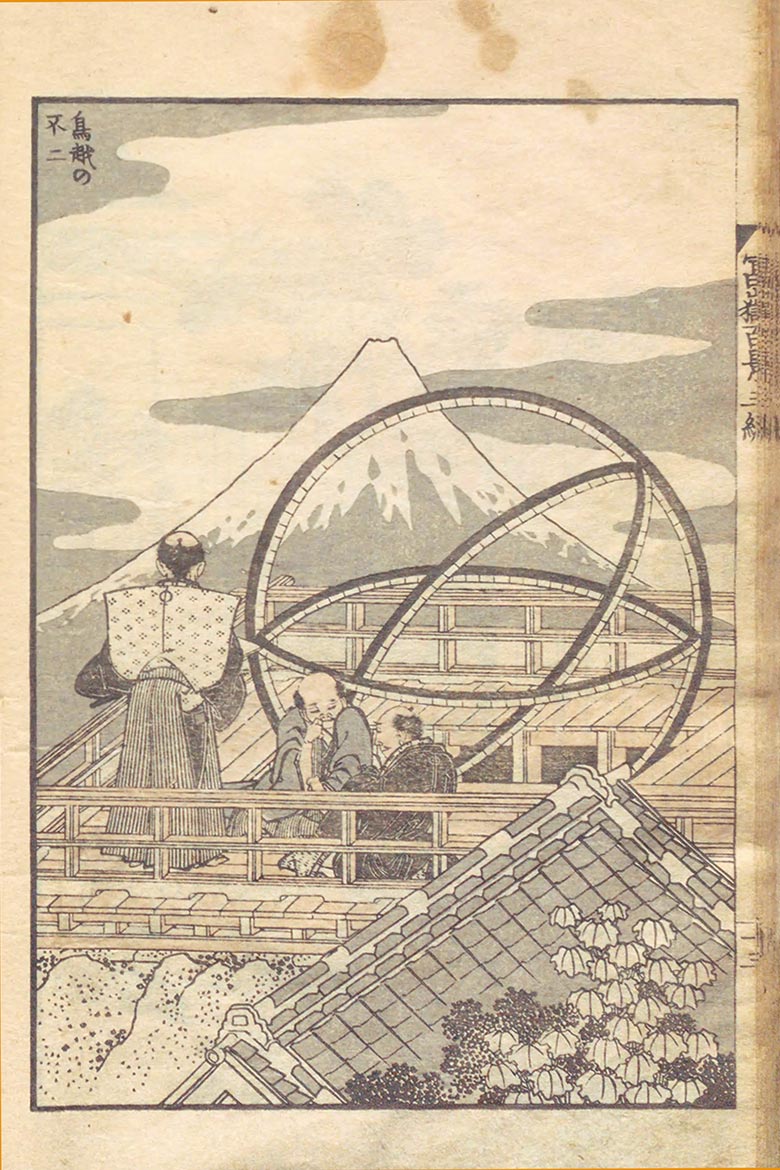

The people of Japan did not stop at merely appreciating outer space as part of nature, however. The construction of astronomical observatories around the 7th century led to the establishment of a calendar system based on factors such as the movement of the sun and the waxing and waning of the moon, and fortune-telling predictions were made in accordance with phenomena including solar and lunar eclipses and the appearance of comets. Murals in the Kitora Tomb thought to have been painted around the late 7th century to 8th century include one of the oldest astronomical charts in the world, revealing that people at the time were observing the celestial bodies and had accurate information on their movements. The introduction of Western knowledge in the 17th century brought further advances in research using telescopes and armillary spheres (instruments for astronomical observation), leading to the establishment of the foundations of modern astronomy.

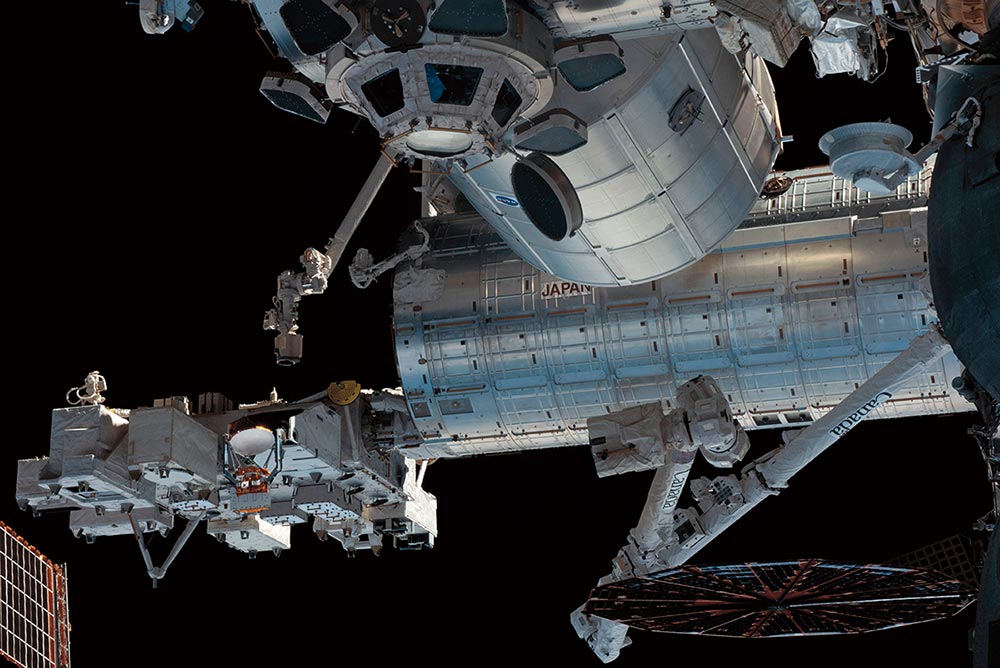

Kibo, an ISS Experiment Module (Photo: JAXA/NASA)

Moving toward coexistence and harmony in space development

Today, with the success of Japan’s independently developed H3 Launch Vehicle and small satellite operations, the country is a global leader counted among the most advanced countries in space development. One characteristic that sets Japan further apart is that it does not view technological development solely in a competitive sense but rather prioritizes cooperation with other counties in peacefully and sustainably utilizing outer space.

The International Space Station (ISS), a multinational collaborative project involving five international organizations, provides an example of this. With the Japan-developed Kibo module playing an important role as a research base and the KOUNOTORI (HTV) unmanned cargo transporter carrying out resupply missions, Japan has performed fundamental support functions for the project and received high appraisals from other countries.

Also, private-sector projects to clean up space debris represent a uniquely Japanese effort to maintain space as a sustainable place. In addition, Japan is actively working to provide technical support to up-and-coming countries involved with space development.

The Japanese view of outer space as an integral part of nature since ancient times seems well reflected in the Japanese approach here, considering space not as a place to pioneer and develop, but as a new venue for coexistence with the people of the world.

Supervised by Futamase Toshifumi

Born 1953. Tohoku University Professor Emeritus specializing in astrophysics. His written works include Nihonjin to Uchu (“The Japanese People and Outer Space”) and Kiso kara Manabu Uchu no Kagaku: Gendai Tenmongaku e no Shotai (“Learning Space Science from the Fundamentals: An Invitation to Modern Astronomy”).