niponica is a web magazine that introduces modern Japan to people all over the world.

2017 No.22

Tokyo, a 400-Year Narrative

Traditional Skills Live On, from Generation to Generation

The culture of old Tokyo has come down to the present day without losing its luster, as the world of crafts certainly shows. Come visit contemporary artisans who embrace tradition with new artistic feeling, while maintaining the skills and sensibilities of those who have gone before.

Photos by Ito Chiharu

江戸切子 Edo Kiriko

Horiguchi Toru was born in Tokyo in 1976. He is active in the foreign exhibition scene as well. “I really want more people to discover the charm of Edo kiriko cut glass.”

Worktables are lined up neatly in the atelier, where white is the predominant interior color. Horiguchi Toru is sitting at one of the tables, pressing a cup against a spinning grindstone. As soon as the cup touches the grindstone, its colored surface is shaved off and sparkling clear light comes through the glass from inside.

Edo kiriko is one type of cut glass, a traditional craft passed down from generation to generation in Tokyo. It is known for its bright colors and gorgeous patterns. Among the many varieties, Horiguchi’s work is especially remarkable—the form is not particularly decorative and appears simple at first glance, but behind that is an astonishingly delicate accuracy. Place one of his glasses in your hands and the attention-to-detail will astound you.

Horiguchi’s refined style is highly praised even among those not involved in the cut glass market. He tackles many projects unrelated to glassware, like interior furnishings for hotels and accessories.

Presenting works that go beyond the boundaries of Edo kiriko, Horiguchi has brought a breath of fresh air to his craft. And yet, his artistic perspective is surprisingly focused on tradition.

“If you really want to know the soul of something, you have to study its history. If I get enough time someday, I want to research the Edo kiriko made many years ago.”

With youthful energy, this artisan is etching new traditions into glass.

The various elements of the lounge interior create a motif defined cohesively by kiriko cut glass. Note the light-and-shade effect achieved by the intricate shapes.

Top right: The lights above the lounge counter are made of glass, each one carved individually by Horiguchi Toru. (Kiriko Lounge, Tokyu Plaza Ginza; photo: Nacasa & Partners Inc.)

Bottom right: Cups decorated with kikuka-mon (traditional chrysanthemum crests). Place one of the tumblers in your hands, or pour in some liquid, or let light shine through—each lifestyle situation creates its own effect.

紋章上絵 Monshou Uwae

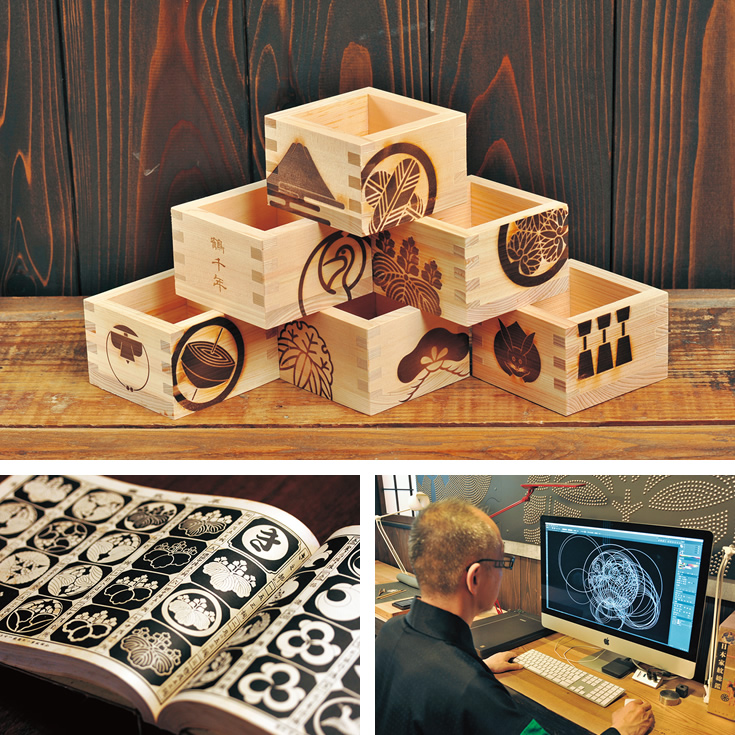

Hatoba Shoryu draws a crest, using a bun-mawashi compass specially made from bamboo. His workshop combines intricate handcrafting from another era with highly advanced digital technology.

A particular kind of monsho (crest) is handed down from one generation to the next within Japan. They are icon-like designs representing the status and lineage of the family, symbols printed on kimono and personal accessories. Monsho uwa-e are crest illustrations drawn by hand on kimono. Hatoba Shoryu is a third-generation artisan in this craft, following the path started by his grandfather. He is keen to try out new approaches, using crest designs for interior furnishings, product logos and more. One of his innovations was to use a computer as a design tool.

“Crest lines are basically composed of arcs,” he explains. “It’s all very mathematically based, and a computer is suitable for that.”

On the computer screen, circles combine with innumerable other circles, creating lines never seen before. Although he uses advanced technology, his crests still show a true appreciation for Japan’s traditional sense of beauty. “When tradition and innovation merge, what interaction will occur? I enjoy thinking about that.”

For the Japanese of today, family crests have a somewhat formal image. Hatoba wants to bring crests into the contemporary mainstream of daily life. His challenge is to carry on an old tradition while seeking ways for family crests to find their place in today’s world.

Left: The masu wooden cup at right in the second row has the Kiri-mon (Paulownia) crest of the Japanese government on its left side and the Aoi-mon (hollyhock) crest of the Tokugawa clan on the right side.

Top right: The Moncho is a register of classic family crests.

Bottom right: Innumerable circles on a computer screen. Only some arcs are selected, to be used as the lines of fanciful crests.