niponica is a web magazine that introduces modern Japan to people all over the world.

2015 No.15

To read the e-book you need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser and a free Flash Player plug-in from Adobe Systems Inc. installed.

Japan, Land of Water

Water: A Natural Asset

Readily Available in Japan

When it comes to water, life in Japan has been quite easy for a long time: just open the tap and out comes lots of good, clean water. The Japanese tend to take it for granted, but in fact a lot of hard work is involved.

Photos: Tokyo Metropolitan Government, Tokyo Waterworks Historical Museum

In Japan, water is safe enough to drink from the tap. (Photo: Aflo)

Sit down in a coffee shop or restaurant in Japan; without you even asking for it, water will soon arrive at your table. Water fountains are everywhere, in government offices and libraries, of course, and in department stores and hospitals, too. Drink as much as you want—after all, it is free! In parks, kids tuckered out from playing will shove their faces under taps and swallow it in big gulps. In cities and towns throughout the country, you will have no trouble finding water to drink, and you almost never have to pay for it.

Everyone takes it as a fact that water is available everywhere, anytime, and always safe and good to drink. Conditions like these help promote the good life in Japan.

Good taste, advanced technology

In the middle of the night, workers listen (with the help of instruments) for water leaking from underground pipes.

So what makes all this possible? The answer is a water supply system that is one of the best in the world, in terms of both quality and output. For example, in Tokyo, the nation’s capital, there is a total of about 27,000 kilometers of underground water mains, enough to reach about twothirds of the way around the planet.

“That’s not to say that the conditions facing Tokyo make it easy to treat and supply safe and great-to-drink water. We have to look after the source, managing and tending large areas of forest. And at the consumption end, we have to maintain and operate the water mains. That requires a lot of hard work and attention to detail,” says an official at the Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Bureau of Waterworks.

Tokyo’s huge population needs a colossal amount of water, and the rivers supplying that water are hardly pristine. So, for example, all filtration plants drawing water from the Tone River employ not only the regular treatment procedures but also highly advanced systems that use ozone and biological activated carbon, and break down and remove odorous and unclean matter.

The results are remarkable. A survey of residents about drinking water preferences discovered that nearly half think tap water tastes better than store-bought bottled mineral water.

Water quality depends a good deal on the condition of the distribution pipes. The Bureau of Waterworks is diligent about maintenance, replacing old pipes according to a regular schedule, and checking for leaks in the middle of the night all over the metropolis. Investigators place one end of a stethoscope-like instrument on the road surface, and listen for the sound of a leak. This helps ensure a low leak rate (around the 2% level over the last few years). The rate is one of the lowest in the world. (It is not unusual for major cities, even in advanced countries, to post rates between 10 and 20%.)

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government uses ozone to treat water. 1: Ozone generator. 2: Ozone contact basin. Ozone is an oxidizing agent capable of breaking down organic matter.

Water access through a pipe network: It started in 1590

Tokyo’s water supply system goes back a long way, to when a project called Koishikawa Josui (Koishikawa Water Supply) was established in 1590. The technology was advanced for its time: stone and wooden pipes or conduits carried water to cisterns, water sometimes even flowed uphill thanks to a siphoning effect, pipes were installed in riverbeds, and a network of water mains was constructed throughout the city (called Edo in those days).

Cisterns were installed in many places for residents to get their own water for drinking and sanitation. We can think of the cisterns as the taps of today—Edo citizens took as much as they needed when they needed it. This all began a good 400 years ago.

Today too, of course, a life with water always near at hand is standard. Just about the first action in the morning is to grab a cup, turn on the tap and drink, and one of the last in the evening is to soak in a full bathtub. Lots of good quality water—that is one way to describe life in Japan.

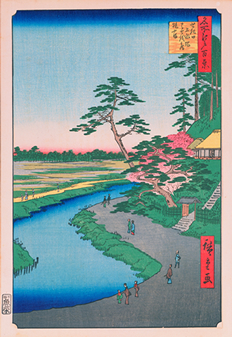

19th-century ukiyoe woodblock print of a scene near a water supply channel in Edo (now Tokyo). Entitled Meisho Edo Hyakkei: Sekiguchi Josuibata Basho-an Tsubakiyama (“Basho’s Hermitage on Camellia Hill beside the Aqueduct at Sekiguchi,” from the artist’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo series), by Utagawa Hiroshige. (Photo: Aflo)