niponica is a web magazine that introduces modern Japan to people all over the world.

2016 No.18

To read the e-book you need to have JavaScript enabled in your browser and a free Flash Player plug-in from Adobe Systems Inc. installed.

Amazing Paper in Japan

Paper in Japanese Culture

Washi: Tradition and Evolution

Paper has played a prominent role in everyday life in Japan, as culture and paper converged in unique ways. These pages offer a perspective on the rich Japanese culture of paper.

From a conversation with Sugihara Yoshinao Photos: Kuribayashi Shigeki Collaboration: Sugihara Shoten

Early beginnings

A scene from Genji Monogatari Emaki (“Tale of Genji Scroll”): Yugiri, from a novel depicting the lives of the aristocracy. The scroll was drawn in the 12th century. (Property of the Gotoh Museum)

Papermaking techniques came to Japan from China, reportedly in the early part of the 7th century. Back then, it was made from hemp. Hemp fibers are very long and tough, and getting them into a workable state requires strenuous, time-consuming cutting and beating. So a switch was soon made to the fibers of native shrubs like kozo (paper mulberry), gampi and mitsumata (paper bush), which are broken down more easily.

Kozo is used for making a pliable yet heavy-duty paper, gampi for a densely woven, glossy product, and mitsumata for a smooth, glossy finish. Hold washi up to the light and you will see how the fibers are intricately woven together. The longer the fibers, the more they are knit together, creating the potential for a sturdy paper. The length of kozo fibers is about 10 mm, while gampi and mitsumata both come in at about 5 mm.

Washi is light in weight, and soft in texture. The fibers tend to ride up on each other, creating opportunity for the formation of tiny layers of air. Although the paper may appear dainty, it is hard to rip, giving it many purposes. The Tale of Genji, thought to have reached its existing form by the early 11th century, included this comment: “Foreign paper is easily torn.” So even back then, people were aware of the strength of washi.

The toughness comes also from the manufacturing method. The nagashi-zuki method interweaves long plant fibers into a uniformly sturdy sheet. The fibers are rocked back and forth in a mixture of water and neri, sticky matter made from tororoaoi (sunset hibiscus) or some other plant having glutinous properties. As the long fibers weave themselves together, liquid is cast out in a repetitive motion until a tough, evenly formed sheet of paper is made.

Papermaking spread through Europe around the middle of the 12th century, and as time passed, artisans switched from hemp to cotton fibers. They used the tame-zuki method, letting water drain out through the mold, rather than casting it out, as in the nagashi-zuki method. This is suitable for short fibers that disperse themselves well in water, but the draining occurs only once, and this tends to result in a paper that is easily torn and uneven in quality.

An inspiration for Japanese culture

One of the Hyakumanto (“1 million pagodas”) made centuries ago (height approx. 20 cm). Each pagoda held one Hyakumanto Dharani, a strip of washi paper inscribed with a Buddhist prayer (below right). (Private collection)

Artisans apparently established the nagashi-zuki method in the Nara period (710-784), when copying and distributing sutra prayers became part of a national campaign to spread Buddhism. This goal required plenty of paper, prompting the cultivation of kozo for the raw material, and the teaching of papermaking techniques in different parts of the country. The Hyakumanto Dharani was a series of one million miniature wooden pagodas, each containing a rolled-up strip of paper with excerpts from a Buddhist sutra printed on it. Those still in existence were printed in 770, making them the world’s oldest printed work. We can assume that production was as huge as it was because artisans had already mastered nagashi-zuki papermaking techniques.

During the Heian period (794-1192) the culture of the aristocracy flowered. Native kana letters were invented, and this encouraged the reading and writing of novels and waka poetry. These were sometimes written on gorgeous paper to highlight the content, using dyes with hues like murasaki (violet), ai (indigo), and beni (crimson). Some paper was ornamented with sprinklings of gold and silver.

The Edo period (1603-1867) was a time when woodblock printing techniques were mastered, not only by illustrators working for the Shogunate, but also by other artisans who made kawara-ban newspapers and ukiyoe woodblock print posters, both of which were produced in large quantities. During the Edo period, then, ordinary people were using paper on a daily basis.

Making washi paper the traditional way. Left: Pulp water is lifted and filtered through a reed screen, using dexterous hand motions. Right: The paper sheets are placed in the sun to dry. (Photos: Mino City Government, Nakata Akira)

A regular part of life

Folded white paper streamer (shide) tied to a torii gate at Shimogamo Shrine, Kyoto. Shide are decorations, but at the same time they are emblems indicating a sacred place. They are similar in this way to the cut paper art on pages 2 and 3. (Photo: Nakata Akira)

Washi came to serve many purposes because it is sturdy, beautiful and highly versatile.

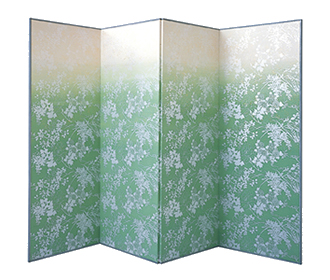

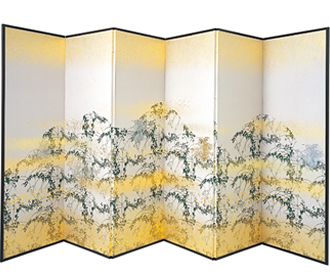

Traditional architecture in Japan would hardly be Japanese without shoji and fusuma sliding screens and partitions. Their use of washi is striking. The shoji latticework is covered with washi, and light passing through it caresses the interior with a touch of nature. Fusuma are covered with decorative paper to define and beautify space.

Washi can be made waterproof and stronger with a coating of persimmon tannin lacquer or oil, for the manufacture of containers, umbrellas and other oftenused products, even items for the wardrobe. Washi, either cut into fancy shapes, folded or glued together, demonstrates its adaptability:

・in annual festivities as tako kites flown at New Year’s, Koi-nobori banners fluttering in the wind in May, and Tanabata strips of paper in summer;

・in games such as Karuta and Sugoroku and

・as decorations for Shinto and Buddhist rites and festivals.

Washi came to play many roles in daily life in Japan, and some live on to the present day.

Among the best-known washi production centers are locations in Gifu Prefecture, where they make a kind of washi called Hon-minoshi, in Shimane Prefecture, where they make Sekishu-Banshi, and in Saitama Prefecture, where Hosokawa-shi is made. These three washi varieties are now on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list. Other varieties deserving mention are Echizen-washi from Fukui Prefecture, a high-quality paper once used for official documents of the feudal military class, and the richly varied Tosa-shi from Kochi Prefecture. The locations are blessed by nature with water that is both plentiful and crystal clear, two requirements for a papermaking industry. The necessity of artisanal expertise has also been passed down by artisans from one generation to the next. Fukui Prefecture is the only place in the world honoring a goddess of paper. She has a shrine dedicated to her, and it is said that her support has sustained the industry there up to the present day.

The future

Handmade washi entered into a decline in the Meiji period (1868-1912), due to the importation of paper from large-scale mechanized factories overseas. The paper we use today is made from fibers about 1 mm long, solidified from a wood pulp mush with the help of chemicals. This makes it suitable for mass production, but also makes it easy to tear and limits the ways it can be used. Washi can still satisfy many needs because of its manufacturing techniques and characteristics. For instance, although Japan’s paper currency is known for the advanced technologies used to print it, less known is the fact that the bills incorporate certain advantages of washi—they contain mitsumata materials for a smooth finish and extra strength, and have watermarks developed by washi makers to prevent counterfeiting.

I often display items made of washi at overseas exhibitions in Paris, London, Milan and elsewhere, seeking to spread appreciation of its charms. Visitors are surprised that a natural material can be used in so many ways. My recent projects include mixing traditional materials with wood pulp or rayon, using machinery to replicate manual techniques, and developing new types of washi for interior decoration and ink jet printers.

The potential continues to grow. And one thing is sure—new varieties of paper for as yet unknown purposes will be developed. They will hold true to the tradition of washi while fitting in with modern lifestyles.

Sugihara Yoshinao

Representative Director of Sugihara Washipaper Inc. Tenth-generation owner of Sugihara Shoten, a wholesaler of Echizen-washi. He plans, manufactures and markets traditional handmade paper that has deep local roots. While maintaining tradition, he is a proponent of new types of washi for the modern age, including washi paper for inkjet printers.