Web Japan > Trends in Japan > Pop Culture > Fascination with Personification

Fascination with Personification

Japanese Creativity Brings Objects to Life as Cartoon Characters

Chôjû-giga (Scrolls of Frolicking Animals) In the collection of Kosanji Temple. Picture supplied by Kyoto National Museum

Enlarge photoThe tradition of giving human characteristics to animals and other objects has played a leading role in the development of the manga aesthetic. Today, the personification phenomenon has entered the mainstream of Japanese culture. Cute, humanlike characters have become a vital part of popular culture and a key element in corporate and government public relations.

Personification—One of the Building Blocks of MangaThe tradition of personification goes back as far back as the twelfth century, when Toba Sôjô depicted rabbits and frogs playing like human beings in Chôjû-giga (Scrolls of Frolicking Animals), now designated a national treasure. This tradition of giving human characteristics to non-human objects has continued to evolve in the modern era.

The beloved Astro Boy by Tezuka Osamu is the most popular of a number of postwar manga depicting machines and robots with individualistic human features. Mega-hits like Anpanman by Yanase Takashi created loveable characters from a variety of unlikely materials. Anpanman himself is a rosy-cheeked superhero with a large round head modeled on a popular Japanese sweet called anpan, a kind of bun filled with bean jam. The series ingeniously personifies Japanese people's fondness for a favorite comfort food as the embodiment of warmth, kindness, and reliability. Anpanman remains a firm favorite with millions of Japanese children.

Trains with PersonalityToday, Japanese personification builds on this tradition with manga-style characters that personify everything from cities and neighborhoods to local landmarks, railway lines, and even computer operating systems. The characters help to bring alive the image that a place or object has in the popular mind, with physical features and a personality to match.

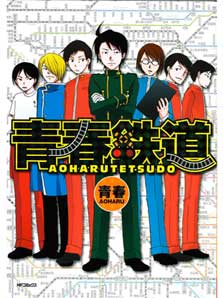

One popular subgenre of the personification craze is inspired by Japan's unparalleled rail culture. The Tokyo rail system is one of the biggest in the world, incorporating dozens of lines and hundreds of stations—each with a personality of its own. A popular manga called Aoharu Tetsudo, brings the system vividly to life, personifying the different lines as young male manga characters with styles of dress and personalities reflecting their reputation among passengers. The series turns clanking metal and spaghetti-like lines on a map into vivid characters with their own unique strengths and weaknesses. The humorous comics embody the feelings of affection that Japanese commuters on the world's most efficient mass transport system feel for the lines and trains that form such a vital part of people's convenient daily lives.

Miracle Train goes a step further. Originally part of a PR promotion to celebrate ten years of Tokyo's Oedo subway line, the series draws the stations as attractive young men with interests and personalities reflecting the areas they represent. The historic riverside area of Ryogoku, for example, home to the national sumo stadium and Japan's biggest annual summer fireworks displays, is drawn as a sporty young man with a fondness for historical novels, fireworks, and the chanko hotpot dishes that are the daily staple of Japan's sumo wrestlers.

What Comes Next?Fujikawa Keisuke, a guest lecturer at Kyoto Saga University of Arts and expert on the history of manga and anime in Japan, suggests that the evolution of manga and anime may be returning to its roots. "It started with simple personification, and then shifted toward human dramas focused on storylines," he says. "Now the tide has swung back to personification and an emphasis on characters again. This could mark the beginning of a completely new generation of manga and anime. I can't wait!"

Japan's tradition of personification ingeniously turns lifeless objects into memorable characters that help to deepen the bonds of communication between organizations and their public, playing a small but important part in making Japanese society the safe, colorful, and creative it is today. (March 2011)

- Mascots Making Waves (March 2009)